“I don’t want to talk about what happened. I don’t even want to think about it. These days, I only want to think about the future,” says 19-year old Ashia resolutely. She is sitting on a cushion on the floor of her temporary home, with her two-year-old son playing with a piece of plastic in her lap. The walls and the ceiling of their shelter are decorated with flower-patterned textiles that move gently in the breeze from the humming desert cooler. She arrived in Arbat IDP camp five years ago, in 2014, after ISIS had taken control over her home region, Saladin. She fled in panic and survived, but many did not – something that is difficult to talk about still. She and everyone she knows in the camp have lost at least one friend or relative, and very painful memories remain.

Ashia spends her days in the shelter, while her husband is at work. The camp is located just outside the town Arbat in Iraqi Kurdistan, roughly 200 km from the Saladin region.

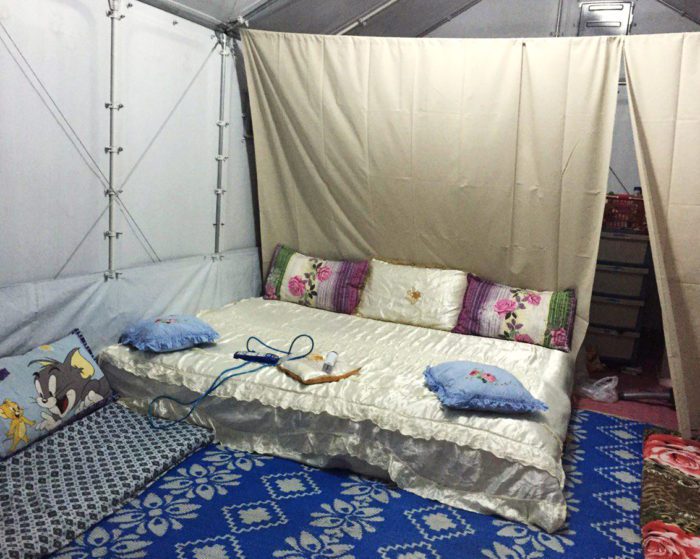

Like the rest of the camp’s residents, the young family lives in a Better Shelter unit with a kitchenette and a separate toilet and shower of their own. It is the holy month of Ramadan, and Ashia will soon start preparing the food for Iftar at sunset. The family purchases vegetables and other groceries from a truck that makes a daily visit to the camp.

Five years have passed since they arrived, and the families have established an everyday life in the camp. Many of the men have work permits and can earn an income in the nearby city of Sulaymaniyah. The children go to school in another camp down the road. “I miss my old life and my friends in Saladin,” says 15-year old Rosul in perfect English, which she studies at school.

It is expected to take at least twenty years to rebuild the larger cities that were attacked during the war. Armed forces reclaimed Saladin in 2016, but just like other liberated areas, the region will face major challenges for years to come. Many families in the camp claim that they want to return home, but before the cities have been cleared of landmines and as long as buildings remain demolished and neither economy nor crucial societal functions have been restored, what is there to return to?

Therefore, many expect to remain in the camp for another few years. The young girls that are playing at the feet of their parents whose housing block we visit are born here in the camp. “We want to return home,” they say, despite the fact that “home” to them is partly an imaginary place, of which they have only heard in their parents’ stories.

The number of Iraqi IDPs (internally displaced persons) returning to their areas of origin has reached 4 million, while approximately 2 million remain displaced.